Having both Mexican friends and Jewish friends in L. A., also having dated a few Jewish women back in my 20's, there is seeming almost-total disconnection between the Mexican communities of largely the Eastside, South Central L. A., and the East Valley and the Jewish communities of the Westside and Southeastern San Fernando Valley. To the casual observer and to many Angelenos, the two communities mix, at best, between Spanish-speaking help and Jewish homeowners. One might as well be talking of Venus and Mars as of Jews and Mexicans, for the amount to which both groups are aware of each other in L. A.

What older Mexican-Americans and Jewish-Americans who were born and raised in Los Angeles know is the strong though unpublicized bond that has existed among Mexicans and Jews since Los Angeles (and California) was part of Mexico. It's still hard for most Americans to wrap around their heads that Jews played a significant role in the settlement and development of the American West. Yes, there were Jewish cowboys driving cattle, many more than the history books and Western movies would tell us.

Jacob Frankfort was the first recorded Jewish person to arrive in the Mexican town of Nuestra Senora la Reina de Los Angeles de Porciuncula (L.A.) in 1841. He stayed long enough to become one of the wealthiest men in that tiny town by the time the U. S. took over in 1847. He went aboard the Peruvian ship, Ascencion, in 1845, docked in San Pedro Harbor, to appraise the ship's contents. He was sent by the mayor of Los Angeles. Frankfort knew enough Spanish by then to do his job. That set the pattern for Mexican-Jewish relations for the next century.

This is the Los Angeles that Jacob Frankfort lived in, 1848, one year after Los Angeles became the United States.

This is the Los Angeles that Jacob Frankfort lived in, 1848, one year after Los Angeles became the United States.There were eight Jewish inhabitants in Los Angeles in 1850, when California became a state and the American city of Los Angeles was created. One of those eight, Morris Goodman, became one of the first city councilmen. He started a tradition that continues today, with councilmembers Paul Koretz, Mitchell Englander, and Bob Blumenfield.

As the city grew, so did the Jewish population. Because the city maintained a Spanish-speaking majority population until the 1870's, Los Angeles' Jewish community knew Spanish and catered most of their business to the Mexican community. This would also occur into the 20th Century with Jewish storeowners, bankers, and other professionals becoming immersed in Spanish-speaking communities and offering their services, often in Spanish. Some of the new Jewish arrivals, such as Joseph Newmark, came to Los Angeles in 1854, made great wealth in farming and ranching, adopted the Spanish Don lifestyle that his neighbors, the Picos, Sepulvedas, Carrillos, and Verdugos had lived. He built an adobe that stood until the 1930's and became the founder of Montebello and his land became Monterey Park. His and other Jewish families were so integrated into Los Angeles culture that Harris Newmark's "My Sixty Years in Southern California" is considered one of the essential histories of early Los Angeles.

The leading Spanish-speaking Californio families enjoyed close relationships with many of their Jewish neighbors. MrLA was astounded one day when, on a tour of the Casa de Adobe in Highland Park, a replica of a typical Californio mansion of the Spanish/Mexican era, a 60-ish woman and her husband were talking about how the wife remembered seeing furniture and cowhides at her Uncle Antonio's house. In conversation, she told me that she and her husband were from one of the oldest Jewish families in Los Angeles. Who was Uncle Antonio? He was Antonio Sepulveda, of THE Sepulvedas, of Sepulveda Blvd. fame. Her father worked for Antonio Sepulveda. Her family and the Sepulvedas were so close, she called Antonio "Uncle Antonio" and grew up visiting him at his ancestral adobe near Culver City.

Yes, most Mexicans were staunchly Catholic and Jews were Jewish. Anti-Semitism was always present in Los Angeles although, among Mexicans, it was never serious enough to prevent close friendships from happening or preventing both groups from living next to each other. It was only dating and marriage between them that proved a consistent conflict between Mexicans and Jews.

For much of L. A. history, little was known of Mexican-Jewish intermarriage. Publicly, such unions were discouraged although there were certainly such unions, whether they were official or unofficial unions. Particularly among Jews, intermarriage was seen as threatening the existence of Judaism. Nonetheless, as the years rolled on, with greater numbers of Mexicans and Jews living next to each other and going to schools together, there would be romances and, extremely so, marriages. MrLA was a teacher's assistant at a Hollywood elementary school in the early 1980's, putting himself through college. He met an older woman named Dolores, who grew up in the San Fernando Valley but was the daughter of a man and woman who grew up, met, and married in Boyle Heights. The father was Mexican-American; the mother, Jewish-American. Dolores told me how her father, a dark-skinned man and her mother, fair-skinned, would not be served in some restaurants in Los Angeles during the 1940's and both families practically disowned them. Despite those and many other bigoted slights, including living Mexican/Jewish in a mainly WASP San Fernando Valley in the 1950's, Dolores' parents remained married, had children, knew their grandchildren, and both families eventually came to accept their marriage. MrLA worked as an elementary teacher in his other lifetime. He was friends with a group of female Jewish teachers who married Mexican-American and other Latino men. These ladies spoke fluent Spanish and were as at home on the Eastside as they were on the Westside, where they were raised. One of MrLA's classmates when he was being certified as a teacher was a woman named Carole, who was from one of the many Jewish families living in Baldwin Hills in the 1960's who married an African-American classmate from Dorsey High School. It might not have been the "epidemic" that the Jewish community in Los Angeles might've thought but there was a lot of mixing going on between Mexicans and Jews in L.A. Like a lot of romantic/sexual activity that is frowned upon by mainstream society, Mexican/Jewish unions were quietly, sometimes, anonymously entered into, sometimes kept on the down low but they happened and happened more often than Angelenos then and now might've realized.

Sephardic Jews are Jews that trace their ancestry to Portuguese and Spanish Jewish communities that existed before they were destroyed by the kings of Portugal and Spain in the 1490's. Like Gypsies, they scattered to many countries around the world. Many would make their way to Los Angeles from the 1850's onward. It could be said that Los Angeles' Sephardic Jews were the bridge that made contact between Mexicans and Jews so easy in Los Angeles. S. K. Labatt and Solomon Lazard were two of the earliest Sephardic Jews in Los Angeles. Not to diminish the contributions of other Jewish communities but the Sephardic community not only influenced the pattern of relationships between Mexicans and Jews in Los Angeles, they left a gigantic imprint on Los Angeles institutions WAY beyond their numbers. Sephardic Jews speak Ladino, a language that is largely 15th Century Spanish mixed with some Hebrew and words from Middle Eastern countries where Sephardics went after their communities in Portugal and Spain were destroyed. Speakers of Spanish and Ladino speak to and understand each other very easily. S. K. Labatt and Solomon Lazard came to Los Angeles and set up shops, selling to the largely Spanish-speaking Angelenos of the 1850's. They communicated with their neighbors easily and became friends as well as business associates of both the Latino Californios and later arrivals of Jewish with non-Hispanic backgrounds. It was Labatt and Lazard that started the first Jewish organization in Los Angeles, The Hebrew Benevolent Association. Among it's achievements was the creation of the first Jewish cemetery in Los Angeles. Located in Chavez Ravine, there's a marker nowadays that marks the site of that cemetery. In 1910, the remains in that cemetery were moved to other, newer Jewish cemeteries in Boyle Heights and East Los Angeles.

Marker Showing Site of the First Jewish Cemetery in Los Angeles

Marker Showing Site of the First Jewish Cemetery in Los Angeles

Solomon Lazard and the Legacies He Left.

Into the 20th Century, Labatt led the way to the creation of two of Los Angeles' iconic hospitals: Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and City of Hope.

Those few of us Angelenos left who grew up in Los Angeles between 1910-1960 remember Boyle Heights as the center of the Mexican community, the center of the Japanese community, the Russian community, the Croatian community, an important African-American and Italian community and, most definitely, the center of the Jewish community. Synagogues, delis, day schools, and Judaica would be found throughout Boyle Heights. Next to the Lower East Side of New York, more Jews lived in Los Angeles than any other city. The community life within the Jewish community was strong. Doctors, lawyers, teachers, political activists came out from Boyle Heights. So did Mickey Cohen and Johnny Stompanato, two of the most infamous gangsters in American history. All her life, Cohen's housekeeper mother would say her son was a good boy, after arrests but the Jewish community of Boyle Heights was one of the first to call President Franklin D. Roosevelt to increase immigration for Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany; call for the creation of Israel; fight to end racial discrimination that kept African-Americans east of Alameda Street and South of Downtown by law; loudly called to end the illegal mass deportations of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans to Mexico during the Depression, etc. It was in Boyle Heights that Alice Greenfield McGrath grew up among Mexicans. Her familiarity and ease with Mexican culture permitted this Jewish woman to raise money for the defense of 12 Mexican-American youth charged with a murder that they didn't commit at a water pit sensationally called "Sleepy Lagoon", a murder case that, along with the Scottsboro Boys, became a hallmark of racism in the American legal system that became the basis for the famous play and film, "Zoot Suit".

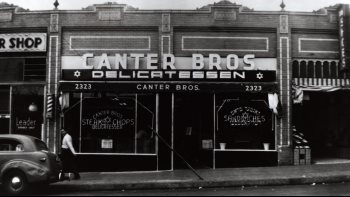

The business and community life in Boyle Heights was a kaleidoscope of cultures and great activity. Anyone remember seeing Dr. Cohen, the credit dentist, whose Downtown L. A. and East L. A. offices catered heavily to Spanish speakers? He did tv ads on KMEX-TV, Channel 34 until the early 1970's. Canter's Deli, the home of hipsters and Hollywood A-list wannabes didn't start life on Fairfax. It started on Brooklyn Avenue in 1931. There are generations, now graying, that remember Zellman's on Brooklyn Avenue (now Cesar Chavez Avenue but named for many Jewish residents who migrated from New York to Boyle Heights in east Los Angeles) and Manny Zelman, the last owner of the store, rooted in Boyle Heights until his was the only Jewish-owned store left in Boyle Heights. Manny and his son, Dean, closed the store in 1999 but Dean Zellman stayed on in Boyle Heights' Neighborhood Council.

If there was such a historic bond between Mexicans and Jews in Los Angeles, why don't we, Angelenos, see that, hear about it, read about it? Why does no one no about it?

After World War II, soldiers of all kinds were offered the G. I. Bill of Rights. They came back from

the war empowered to do things they would not have had the idea nor the money to do, such as buy homes. With the end of racial covenants in California, which allowed legal segregation by giving homeowners rights to refuse to sell to non-whites and non-WASPs, Jews, Mexicans, and African-Americans could move to the new housing developments. Jews moved out of Boyle Heights to the Fairfax area and the Westside, generally. Mexican-American veterans and their families moved eastward and southward into housing developments in Pico-Rivera, Montebello, Commerce, Downey, and Paramount, among others, creating not just a physical distance but a physical and cultural divide so great that future generations of Mexican- and Jewish-Americans no longer interacted nor knew of each other. The younger generations of those groups are not, generally, conscious of each other's existence, as their grandparents had been.

As those families left Boyle Heights, a steady, constant stream of Mexican immigrants used Boyle Heights as a "port of entry", their place of settlement after arriving from Mexico. So, for generations, Boyle Heights was all but turned into a Mexican city. The poverty that comprises much of the Boyle Heights community and media focus on gang crime in the area have, until the last 5 years, stigmatized Boyle Heights, causing Westside and Valley Jews to not see any need to visit Boyle Heights, viewing the community as threatening and the Boyle Heights community viewing the Jews with suspicion and bewilderment.

Since World War II, waves of Jewish migrants from other American cities and Jewish immigrants from other countries have settled in Jewish communities on the Westside and the San Fernando Valley. Not having grown up in Los Angeles and not having much daily contact with Mexicans, the Mexicans were now seen as the "other", a foreign, untrustworthy, even culturally/racially inferior group of people that best stay in their neighborhoods, not the cordiality and equality that had characterized Mexican/Jewish relations in Los Angeles.

As the per capita incomes of Jewish and Latino Angelenos have grown more unequal over the last 60 years, the dynamics of class, language, and race differences inform the interaction most Mexicans and Jews now have with each other: one of Jewish boss/Mexican (or other Latino nationality) worker. The nannies, gardeners, housekeepers, and landscapers of many Westside and Valley Jewish middle/upper middle class homes have been Mexican immigrants. While cordial relations can and do exist in these situations, the relationship is that of employer/employee, not as peers, as had been the case between Mexican and Jews in Los Angeles until World War II. That has inhibited the mixing and understanding of one group by the other.

Because Los Angeles has grown so exponentially, in size and in population, since the end of World War II, communities tend to live in "bubbles", areas that people have marked for work, living, and recreation that create a personal and community living space so walled-in because there are miles that have separated ethnic communities from each other, living parallel lives without intersecting each other.

Canter's Deli, in Boyle Heights, circa 1940.

Mural Depicting Historic Relationship of Mexicans and Jews, at Canters Deli, Fairfax Avenue

Breed Street Shul, (Congregation Talmud Torah), Oldest Synagogue in Boyle Heights. Now a community historical interpretive center for the history of Boyle Heights.

Zellman's Men's Wear, Circa 2000, on Cesar Chavez Ave. (Ex-Brooklyn Ave.)

Things are not so grim now as they appeared only 5 years ago for Mexican and Jewish Angelenos.

Gentrification of formerly poor, dilapidated neighborhoods has aroused great controversy in the last 5 years but it has also brought about changes in demographics and social/community interactions not seen in 60 years. The hipsters of 2015 are a varied group of mainly 20-30 year olds but of various races and ethnicities. The commercial, artisitic, and architectural renaissance of Hollywood, Silver Lake, Echo Park, and, increasingly, Boyle Heights, have the hipsters and other affluent people moving into communities once feared, now cool, trendy, and bringing cultural communities once isolated from one another into living, working, and eating with each other. The hipsters, who come from the Westside, the Valley, and from all over the United States, no longer look only to Hollywood and the Westside as their "port of entry" into living in Los Angeles. The fears that kept Jews and Mexicans away from each other for decades have largely faded away as the different ethnicities living in gentrified communities see themselves as fellow artists, music lovers, peers, than they has been the case for decades. The descendants of Jews that lived in Boyle Heights have spearheaded a consciousness among L. A. Jews of the rich Jewish heritage of Jewish life in Los Angeles and the importance that Boyle Heights has played in rediscovering the history of multicultural harmony among Los Angeles' ethnicities, renewing a particular pride in being a Los Angeles Jew that does not play second fiddle to New York, Chicago or Israeli notions of Jewish life.

The new fusion brought about by gentrification has created foods that exist only in Los Angeles: Korean Tacos, breakfast sushi, iced green boba tea, and the Kosher Burrito. There is Mexikosher, a kosher restaurant serving kosher versions of Mexican food over on the Westide, near Pico and Robertson Blvds., owned and operated by Japanese-Mexican chef, Katsuji Tanabe. Only in L. A., right? www.mexikosher.com

While much more community bridge building between the Mexican and Jewish Angelenos still needs to occur to overcome the separation, isolation, and mistrust of the two communities over the last 70 years, the man who symbolizes Los Angeles to us and to the world, Mayor Eric Garcetti is, himself, the physical embodiment of the relationship between Mexicans and Jews in Los Angeles. Actually, Mayor Garcetti embodies the foundations of Los Angeles by being of Mexican, Italian, and Jewish descent. Since his administration has called attention to and promoted multicultural living in Los Angeles, the future looks bright for Angelenos to experience the very old and special relationship between the Mexicans and Jews of Los Angeles.

Hasta la vista, Booby!